The Digital Sublime: The Awe & Terror of New Media Landscapes

This article originally appeared on Agora Digital Art

Words by: Gabriella Gasparini | Ed Kiran Sajan

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, still frame from The Wilding Of Mars, (2019)

What upsets our sense of harmony, self-preservation and spatiotemporality but, at the same time, fascinates us with a chaotic yet oddly satisfying sense of awe? Well, if it isn’t the age-old experience of the sublime yet again! You might have heard the term ‘sublime’ being used as an adjective to describe excellence in the real world (puts on a fake accent) “oh darling, your cupcakes are simply sublime!” but in the more abstract and decidedly more contortuous realms of philosophy, the expression takes on a whole different meaning. In fact, philosophers have been squabbling over the meaning of the sublime since the 1st century AD and today, the Sisyphean aesthete has perhaps not-so-much-on-a-whim decided that the sublime is to be in vogue again. But why the big fuss over a concept so old?

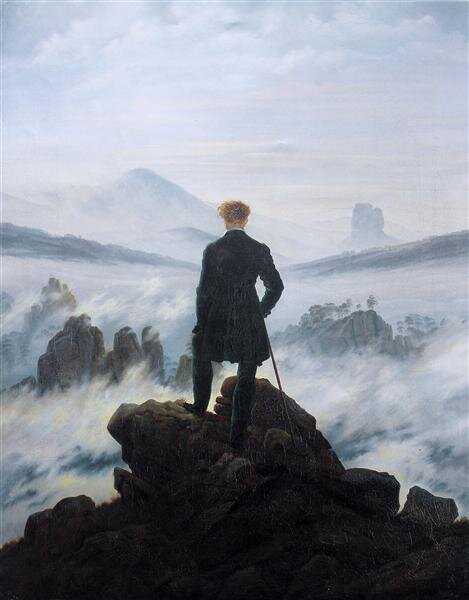

Today, amidst the flurry of information, data and shifting landscapes, we find ourselves closer to new realities so infinitely complex, far-reaching and vast that we struggle to comprehend them in our mind. Timothy Morton calls these ever-so-vast and uber-powerful systems hyperobjects, and goes on to use this term to label the internet, climate change or radioactive decay as examples of processes which cannot really be seen but, in return have a powerful effect on us. In terms of the sublime, these are experiences that, as the 18th century philosopher Edmund Burke rightly affirmed “suspend our motions, with some degree of horror” in other words, or better still, for lack of better words, we remain stupefied and shocked. In the time Burke was alive, the sublime was experienced when faced with that one massive thing the industrial revolution was trying to tame: nature. Nature, with its dangerously enticing oceans and gorgeously frightening gorges, represented that ‘other’ which humans could not possess: the stark indifference and brute (but beautiful) violence of the natural forces.

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer, (1818)

Our attraction to the Dionysian excesses of the natural world didn’t just entice us further into the jungles, mountains and forlorn beaches because of their rugged beauty. Nope, according to Kant, it wasn’t even really about nature in the first place, it was all about how our mind desired to be challenged. Kant argued that our attraction to the experience of the sublime in nature stemmed from the build-up of sensory data causing our imagination to run wild. In other words, our imagination prevents our faculty of reason from understanding the experience, but, in a plot twist worthy of any romance novel, this very tension provided by our imagination allows us to better understand the concepts of freedom, infinity and transcendence. So despite being shocked and a bit frightened by this unknown at first, we then feel somewhat reassured by our mind’s ability to regain control over the event. Nature was something that could be tamed after all, and the machines of the post-industrial age with their colossal steel beams and powerful turbine engines surely confirmed it. The ‘other’ we were after, perhaps wasn’t in nature after all but rather in the machines our vast and powerful imagination had created. Yet, like a stubborn child whose favourite colour switches from blue to green on a whim, the search for this sublime ‘other’ continued. What infinite representations of sublimity could our minds conjure this time? What exactly are the limits of our imagination? It is here, nestled between the synapses of our consciousness and the axons of our unknown drives, desires and needs that we find the new sublime.

Jon Rafman, still frame from Dream Journal, (2016–19)

The powerful depths and enormous breadths of our imagination have brought us to the creation of new worlds, new fertile playgrounds for our intellect to be stimulated, frightened and amazed. It is no longer necessary to venture into nature or construct gigantic totems to the deities of machinery — I believe the new sublime is flat. In fact, technology keeps getting thinner as we speak, with the latest model of television measuring just 2.55mm. The thrills, awes and astonishments of the contemporary sublime are to be experienced in increasingly flat landscapes that, ironically, wish to be as 3D as virtually possible! The sublime no longer resides in nature and definitely not in machines, for the computer’s outer shell most certainly isn’t conveyant of power nor infinity! Yet through it, we are granted the experience of the digital sublime, that which is so grandiose, powerful and vast in its flatness that we sometimes even think of it as godly. So what keeps pushing our imagination to new flat expanses of creation? Within digital art, the digital sublime is what we experience when caught in a temporal nonlinear expanse such as the one presented by Jon Rafman’s Dream Journal. The digital sublime is in the anthropo-scenic bestial transmutations of Eva Papamargariti’s digital art, which re-imagines form, structure and colour to create eerily mutated entities. It is the encounter with the now merged biological and technological worlds in the biotechnological utopian landscapes of Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s Wilding of Mars. If the sublime is about expanding our imagination and coming just a little bit closer to that scary unknown, then what can we expect the future sublime to look like? We are capable of conceptualising grandeur, vastness and infinite power and as conscientious creatures, our focus should be on the creation of works that not only attract us aesthetically but also motivate us to use this creativity to do good. It is no longer a battle between nature vs nurture or people vs the machines. The flat sublime I propose here invites for a merging of these realms in order to live symbiotically, sustainably and, most importantly, forever creatively.

Eva Papamargariti, still frame from Liminal Beings, (2019)